Classical physics in a spin

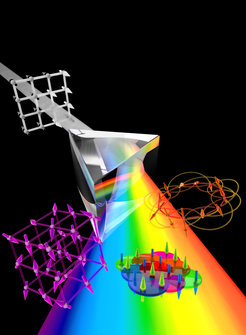

Simple “spin models” used to explain magnetism can precisely reproduce any possible phenomenon in classical, non-quantum physics, according to scientists at the MPQ and UCL.

This is the first time such simple ‘universal models’ have been found to exist. The study, published this week in Science, builds on pioneering work from the ‘80s which is at the interface between theoretical computer science and physics. Extremely simple computers are universal: they can in principle compute anything that can be computed. These new results show that something analogous occurs in physics.

Spin systems are a very simplified, stripped-down model of the interactions between particles making up a material. In the simplest of these models, each particle or “spin” can only be in one of two possible states: “up” or “down”. The interactions between neighbouring particles try to align them either in the same or in the opposite direction, which is known as the Ising model, after the physicist Ernst Ising who studied it in his 1924 PhD thesis.

“Models in different dimensions or with different kinds of symmetries show very different physical behaviour. Our study shows that if one considers models with irregular coupling strengths, all these differences disappear as they are all equivalent to universal models,” says Dr. Gemma De las Cuevas from the MPQ, Munich.

Previous work by Dr. De las Cuevas and others pointed the way, by showing something similar occurred for thermodynamic properties in more complicated models. This new work shows that the result holds for all of classical physics and for much simpler models. Moreover, by connecting the underlying physics to complexity theory – a branch of theoretical computer science – the results also explain where this universality comes from, and tell us exactly which models are universal and which are not.

“These results will perhaps not surprise computer scientists, who are used to the idea that universal computers can simulate anything, even other computers,” said co-author Dr Toby Cubitt from UCL Computer Science. “But the fact that a similar phenomenon occurs in physics is much more surprising, and this insight has not been applied in this way before. We are realising as a community that ideas from theoretical computer science can give us deep insights into physics, backed up by rigorous mathematical proofs. It’s a very exciting time to be working at the interface between these fields!”

He added, “This is not the same as the well-known phenomenon of ‘universality’ in statistical physics. In a sense, it’s the exact opposite. Universality explains why many different microscopic models all behave in the same way, whereas our universal models can behave in all kinds of different ways – in fact, in all possible ways!”

“Spin models are not only used in physics, but also to model other complex systems, such as neural networks, proteins or social networks. All these systems can be modeled by objects (such as neurons, aminoacids or persons) that are interconnected with and influenced by each other,” says De las Cuevas. The new results may hence allow to gain insights into these other systems too.

The researchers are now exploring whether their theoretical findings can be applied in practice to improve numerical simulations of many-body systems. Or to help engineer, in the laboratory, novel complex systems previously thought to be beyond the reach of current technology.

The research has been funded by the EU integrated project SIQS, the Royal Society (UK), and the John Templeton Foundation.