Korean roots, Canadian passport, at home in Garching

„With physics I can explain almost everything around me.“

Annie Jihyun Park is a PhD candidate at the MPQ. Korean-born with a Canadian passport, she now works in Garching, where she develops a simulation experiment, with which she can explore the interactions between atoms. A very complex quantum physical investigation. But for a long time, she never would have thought that she would end up in physics let alone in quantum physics.

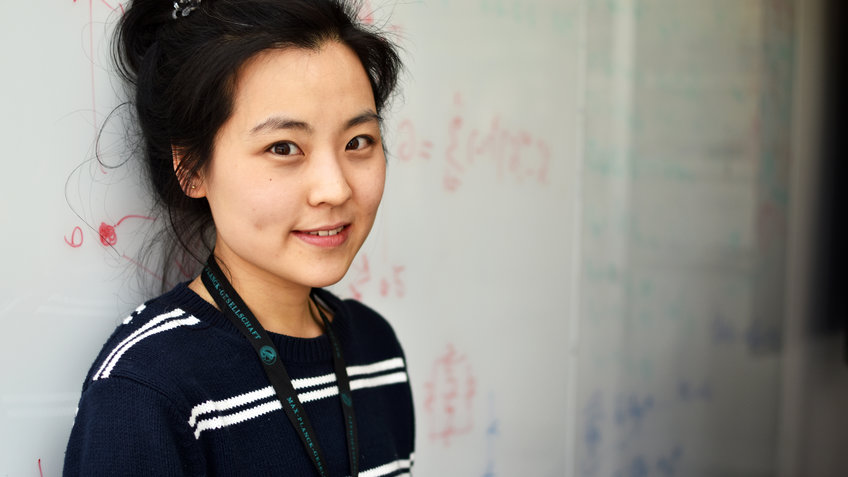

Annie Jihyun Park is in her office on the first floor of the MPQ. She is small and slender, wearing black jeans, a black turtleneck and Birkenstock. "Hi, I'm Annie," she says and smiles.

Today, she is one of the many highly talented young physicists at MPQ and works as a PhD Candidate in the Quantum Many Body Division, supervised by division director Immanuel Bloch and senior scientist Sebastian Blatt. Sebastian is one of the many supervisors at MPQ. For her thesis, she works with ultracold strontium in optical lattices with the aim of building a new quantum simulator. “If I should explain in a very simple way what I do, I would say that I am investigating physical phenomena on very, very small scales. And on these very small scales the physical laws that we observe in everyday life no longer apply. In fact, completely different laws apply. That's what fascinates me. And our apparatus will open up a new way of probing these phenomena,” she says with shining eyes.

For a long time, it was unpredictable that her path would lead her to physics, quantum physics, and optical quantum physics eventually. Because it was only later in her life that she finally discovered her dedication to physics.

At the age of 15, Annie moved from Korea to Vancouver, Canada with her parents and two siblings. Her father is an engineer. Her mother, who is not working, was the one who pushed for the move: It had all been planned well in advance. "It took us almost ten years to get a visa," says Annie. "My mother always wanted the best education for us and decided that we should go to Canada to grow up in a more international environment.” But she wasn’t what some call a “tiger mom”: "She never put pressure on us, the most important thing for her was, that we find something that we enjoy." The move was the most difficult for her father: “When he was looking for a job, everyone wanted references that he didn't have. So he had to start all over again.” Annie didn’t struggle to adapt to the new country: "I understood English well, even though at first I was a little shy and didn't dare to speak." After school, she began studying sciences at the University of British Columbia, which is common in Canada, where you don't specialize so early. Her goal was to start a master in biology or enroll in medical-related studies. Physics wasn’t at all on her mind. It may have been because there were no role models in physics around me, so she didn’t consider that field for herself: “You know doctors and pharmacists and maybe even biologists. It is very unlikely to meet a physicist and especially a physicist who works in research in everyday life, when you’re still at school.” Physics wasn’t an easy play for her only when she started studying for her final exams, which touched upon natural sciences in a broader way. But still, it was a turning point:

“I always told my friends: 'When I am done with this exam, I will never do physics again.' But while learning I suddenly understood that I can use physics to explain everything that surrounds me, especially the physics of sound and music. I was absolutely amazed.”

That’s when she decided to study physics and to complete a master's thesis in quantum physics, still in an area that had nothing to do with optics. Also a PhD was quite clear to her at that time, but not where and in which field of quantum physics. She systematically approached the search for her thesis topic and attended all the colloquia at her institute. She found that she was particularly fascinated by quantum optics and asked her supervisor where to find the best working groups in the field. "He told me: 'You have to go to the MPQ, no matter which research group," Annie remembers. She followed the advice and first entered the institute for an internship for a year ahead of her doctorate.

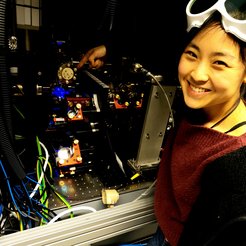

Today, she only takes a couple of steps from her office to the laboratory which contains the machine Annie has been working on and with for more than three years now: “I like to spend a lot of time in the laboratory. Often also on weekends, but voluntarily. I really like being here."

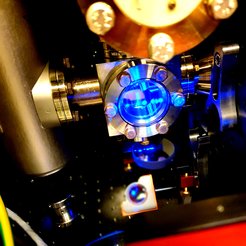

“See the blue light? That's the laser we use to cool hot atoms to one millionth of a degree above absolute zero. At this temperature, atoms show off their quantum mechanical nature while interacting with each other. By controlling them with several lasers, we can even engineer states of matter which we do not find in nature. For better or for worse, this machine brings us new surprises every day!”

Annie’s goal is to find out how the atoms relate to each other when there are many. Unlike other research groups in the department of MPQ director Immanuel Bloch, to which her research is assigned to, her research group works with strontium. Strontium has two electrons on the outer shell. The other atoms usually used at MPQ have only one electron. This complicates the simulation a bit but provides new information that otherwise would not be revealed. For her experiments, she cools down the atoms in a vacuum to a very low temperature, close to absolute zero, in order to prevent them from moving. Also, cooling has the pleasant side effect that the atoms start behaving like electrons, revealing the quantumness. She builds a grid out of laser beams which one can imagine exactly like an egg carton, except there are no eggs: walls and partitions form the beams and atoms sit in every well. By constantly changing the laser grid by a little bit, she can learn about the behavior of every individual atom.

That in itself sounds complicated, but the real crux is that the machine able to create the exact conditions necessary for her experiment does not yet exist. Developing this machine is the core of her doctoral thesis: she needs a vacuum chamber in which the prevailing conditions are comparable to those in space. It needs to be at an extremely low pressure to isolate the atoms from the environment. Then it is time to select and arrange the lasers. "Sometimes I feel like I'm an engineer rather than being a physicist," Annie says, laughing. Building her machine takes about three to five years – exactly the time frame one usually needs for a doctoral thesis. "But I don't have to wait for the machine to be finished, I can do experiments while I'm developing it," says Annie. And it’s working, as her growing list of publications can tell.

“The MPQ is full of collaboration: students, postdocs, and technicians all work together in the lab, with guidance provided by Immanuel Bloch and Sebastian Blatt, the senior scientist in the lab."

Outside the institute Annie lives in one of the MPQ’s own guest houses: "I like to live with the other researchers, I'm at the institute in no time and there's also nature around here". She rarely commutes to Munich, only once a week she’s taking the train to the city for a ballet class. Her siblings are now back in Korea, her sister, who is two years older, works as a pharmacist, and her little brother, who is four years younger, is studying dentistry. “My sister was always homesick for Korea and my brother always felt that he never really got to know his country of origin, so they wanted to go back. That was not the case with me. Maybe I was lucky enough to be just the right age when we moved to Canada,” she says and adds: “When I fly to Canada, it feels like coming home. And now it feels a bit like home every time I come back to Garching.”

(AE/KJ)