Solid-state photonics goes extreme ultraviolet

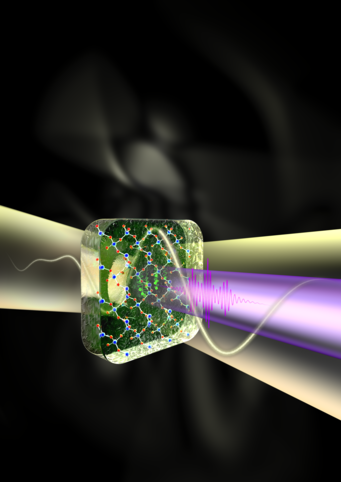

Using ultrashort laser pulses, scientists in Max Planck Institute of Quantum Optics have demonstrated the emission of extreme ultraviolet radiation from thin dielectric films and have investigated the underlying mechanisms.

In 1961, and only shortly after the invention of the first laser, scientists exposed Silicon dioxide crystals, (also known as Quartz) to In 1961, only shortly after the invention of the first laser, scientists exposed silicon dioxide crystals (also known as quartz) to an intense ruby laser to double its frequency, i.e., to change its colour from the visible to the ultraviolet, marking the advent of nonlinear optics and photonics. Now, researchers around Dr. Eleftherios Goulielmakis of the Attoelectronics Research Group at the Max Planck Institute of Quantum Optics in Garching, flashed an intense ultrashort laser pulse on thin films of the same material as in the mentioned pioneering experiment, and succeeded to convert laser light into radiation having a frequency more than 20 times higher than that of the laser, i.e., into the extreme ultraviolet range of the spectrum. The laser pulses used comprised merely of a single oscillation of their wave cycle and allowed the scientists to drive the motion of electrons inside the crystal lattice extremely fast. As the electrons of the material bounced on the lattice potential formed by the atoms in the crystal, they radiate and thus convert the energy taken up by the laser light into extreme ultraviolet radiation. The experiments pave the way towards new solid-based photonic devices. Because the motion of the electrons driven by the laser pulse probes the properties of the solid, measurements of the emitted radiation lead to a deeper understanding of the structure and the inner workings of solids. (Nature, 28 May 2015)

Nonlinear optics and its wide range of modern applications in fundamental science, laser technology, telecommunications and medicine rely on the conversion of light from one colour to another, a process which takes place when an intense laser interacts with matter. Such processes allow one to generate laser-like radiation of frequencies (colour), which cannot be directly produced in lasers and hence to exploit it for new applications.

For more than two decades scientists have utilized very intense lasers to drive the motion of electrons in atoms or molecules in the gas phase such as to produce radiation in the extreme ultraviolet or even the x-ray part of the spectrum. “In condensed phase media — which comprise the basic pillar of modern fundamental and practical photonic applications — things are much more challenging”, says Goulielmakis, leader of the research group. Solids cannot stand intense lasers without being damaged, and even worse, the fast vibrating atoms inside a solid randomly collide with the laser-driven electrons preventing the generation of coherent, laser-like radiation. By using extremely fast laser pulses (typically less than 2 femtoseconds) — so fast as to comprise only a single oscillation of a light wave generated by a “so-called” light field synthesizer — the MPQ scientists succeeded to sidestep these challenges. “Matter can stand intense field when illuminated for a very short time to produce extreme ultraviolet, and atoms merely move within this short time scale”, says Tran Trung Luu, scientist in the team.

But the MPQ scientists didn’t stop there. “We exploited the emitted EUV radiation to unveil information about the structure —more specifically the conduction band dispersion— of the solid which was earlier inaccessible to solid state-spectroscopies”, Goulielmakis points out. Being exposed to the optical fields the electrons get a kick from the valence band to the conduction band where they are accelerated by the laser field. “As the electrons move, they “feel” the surrounding structure of the solid, and this information is embodied in the emitted radiation”, says Manish Garg, a scientist in the team.

But how fast do electrons oscillate to produce extreme ultraviolet radiation in a solid? This is revealed by the frequency of the emitted radiation and the theoretical interpretation of the experiments. “We have a strong indication that the laser pulses force the electrons to perform extremely fast oscillations of tens of Petahertz (1015 Hz) frequencies inside the crystal,” Goulielmakis explains. “In fact, this is the fastest electric current ever generated in a solid, and the emitted radiation from these oscillations allow us to peer into the dynamics of this extremely fast motion.”

By manipulating the waveform of the laser pulses with the light field synthesizer, the scientists also succeeded to control these ultrafast electric currents inside the solid. “Our work opens up new routes for realizing light-based electronics operating at multi-PHz frequencies,” Dr. Goulielmakis resumes. Olivia Meyer-Streng