Nobel Prize Technique on a Chip

Team of scientists at MPQ generate frequency comb with microresonators on a chip for the first time

The frequency comb technique invented at the Max Planck Institute of Quantum Optics (MPQ) in Garching, Germany, has influenced and advanced basic research as well as laser development and its applications to such an extent that in 2005 its inventor Theodor Hänsch (MPQ) was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics together with his US-colleague John Hall. The high-precision measuring instruments for determining optical frequencies have meanwhile been made relatively compact and become commercially available. Much handier, however, is the just 75 micrometres in diameter microresonator with which Dr. Tobias Kippenberg and co-workers from the ‘Laboratory of Photonics’ at MPQ succeeded in generating frequency combs (Nature, 20 December 2007). Frequency combs on a microchip could revolutionize time measurement and data transmission techniques.

A frequency comb is in principle a kind of ‘ruler’ with which unknown optical, i.e. very high, frequencies of light can be determined with extremely high precision. The concept investigated by Hänsch and Hall is based on a mode-coupling process in short-pulse lasers. This produces laser light containing about 100,000 closely spaced spectral lines whose frequency distance is always equal and known with extreme exactness - hence the designation ’comb’. The superposition of this comb with another laser beam results in a pattern from which the unknown laser frequency can be determined with hitherto unattained accuracy. This conventional set-up of a frequency comb consists of very many optical components and is therefore very bulky.

The independent Max Planck junior research group of Dr. Tobias Kippenberg – since 2007 also funded by a “Marie Curie Excellence Grant” – has now in cooperation with Ronald Holzwarth from Menlo Systems (this offshoot company established by MPQ is meanwhile marketing the frequency comb technology worldwide) succeeded in generating a frequency comb by means of a tiny microstructure. In their experiment the scientists use a toroidal glass resonator with a diameter of just 75 micrometres that is produced on a silicon chip at the Chair of Solid State Physics (Prof. Jörg Kotthaus) of Ludwig Maximilian’s University (LMU), Munich. By passing a laser beam in a “nanowire” made of glass close to it they couple light into this monolithic structure.

Such optical resonators can store light for a relatively long period. This can lead to extremely high light intensities, i.e. photon densities, at which a great deal of nonlinear effects occur. And it is such a nonlinear ‘Kerr effect’ that makes it possible to realise a frequency comb: In a 4-photon process two light quanta of equal energies are converted to two photons of which the one light quantum has a higher energy, the other a lower energy than the original one. Here the newly produced photons can in turn interact with the original light quanta, thereby producing new frequencies. From this cascade there emerges a surprisingly broad spectrum of frequencies without any resort to amplification by an active laser medium, as is necessary in the conventional method. “It is noteworthy that there had been no mention in the literature that frequency combs could be generated in this way”, states Pascal Del’Haye, a Ph.D. student at the project. “What we have here is a completely new and surprisingly efficient generation process”, confirms Dr. Tobias Kippenberg.

The new method, however, is only suitable if the distances between all of the frequencies produced are always exactly equal and in this way yield a perfect comb – although the microresonators themselves do not have a perfectly equidistant mode spectrum. In high precision measurements Ph.D. students Pascal Del’Haye and Albert Schließer compared the spectrum of the monolithically generated frequency comb with a commercial version provided by the Menlo Systems company. They showed that the frequencies produced in the microresonator are equidistant, and were able to rule out deviations of as small as 10-18 of the light frequencies.

This new type of frequency comb could be used in the future for optical frequency measurements and also for designing clocks of extremely high precision. Another highly interesting field of application is in optical telecommunications: Whereas in the conventional frequency comb the lines are extremely close and of very low intensity, the approximately 130 spectral lines of the monolithic frequency comb have a separation of about 400 gigahertz and powers of the order of one milliwatt (0 dBm). This spacing and power level corresponds to the typical requirements for the “carriers” of the data channels in fibre-based optical communications. Whereas every frequency channel has hitherto needed its own generator with its own laser, the novel device would make it possible to define a large number of data channels with one single monolithic microcavity.

Not all aspects of the process have as yet been clarified, and the technique has still to be elaborated before the frequency comb can be put into practical application. In view of its high application potential the scientists have nevertheless already applied for patents worldwide.

The work recently presented in Nature was conducted in the context of the “Nanosystems Initiative Munich” cluster of excellence, whose objective is to develop, research and apply functional nanostructures in medicine and information processing. [O.M.]

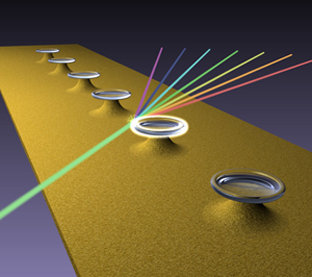

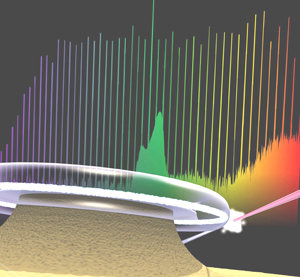

Artistic view of the frequency comb generation within a silica microtoroid: Left figure: Light of one single frequency, symbolized by the green line on the left side, is converted to a frequency comb within the microresonator, pictured by a bunch of coloured lines on the right side of the image. Right figure: Unlike the colourful spectrum that is created by sunlight sent to a prism, the spectrum of light generated by a microtoroid contains certain lines with exactly equidistant frequencies

Contact:

Dr. Tobias Kippenberg

Max Planck Institute of Quantum Optics

Hans-Kopfermann-Straße 1, 85748 Garching

Phone: +49 (0)89 / 32 905 -727

E-mail: tobias.kippenberg@mpq.mpg.de

http://www.mpq.mpg.de/k-lab/

Dr. Olivia Meyer-Streng

Press & Public Relations

Max Planck Institute of Quantum Optics

Phone: +49 (0)89 / 32 905 -213

E-mail: olivia.meyer-streng@mpq.mpg.de