Approaching the Quantum World

Using resolved sideband cooling combined with helium cryostats MPQ scientists get close to the quantum limit of the eigenmodes of mesoscopic mechanical oscillators.

The observation of quantum phenomena in macroscopic mechanical oscillators has been a subject of interest since the inception of quantum mechanics. It may provide insights into the quantum-classical boundary and allow experimental investigation of the theory of quantum measurements. In spite of great efforts, the minute displacements associated with quantum effects, and the random thermal motion of the oscillator have as yet precluded their direct observation. As a team around Prof Tobias Kippenberg (leader of the independent Max Planck junior research group “Laboratory of Photonics and Quantum Measurements” at Max Planck Institute of Quantum Optics in Garching and tenure track assistant professor at the ETH Lausanne (EPFL) in Switzerland) reports in Nature Physics (Advanced Online Publication, 7 June 2009, DOI 10. 1038/NPHYS1304) the ultimate quantum ground state of mesoscopic mechanical oscillators now seems to be in reach: Using a combination of cryogenic pre-cooling and resolved-sideband laser cooling the scientists were able to cool a microresonator down to a temperature that corresponds to about the 60-fold energy of the ultimate quantum ground state, and to reach a sensitivity in the displacement measurements of its mechanical vibrations that is only a hundred times above the fundamental Heisenberg limit.

A mechanical oscillator is an incarnation of a generic physical system, a harmonic oscillator. At the same time, it is, like a mass-on-a-spring or a simple pendulum, a part of every-day life. While it is generally experienced as a “classical” system, the physical theory of quantum mechanics predicts surprising effects both for the mechanical oscillator itself and for measurements made on it. For example, quantum mechanics dictates that such an oscillator fluctuates randomly around its equilibrium position - it basically never is at rest. At elevated temperatures, this may be due to the random kicks it experiences by hot gas molecules surrounding it, or the thermal Brownian motion of the molecules the oscillator is made of. However, according to quantum mechanics, the oscillator still has a non-zero motional energy even at zero temperature, and is therefore expected to still move randomly with minute amplitude. Even more, if one wants to measure the position of the oscillator, quantum mechanics requires that this disturbs its motion and makes it fluctuate even more. This so-called “quantum backaction” limits the sensitivity available in a displacement measurement, and gives rise to the “Heisenberg uncertainty limit”.

So far, such effects have never been experimentally observed. Probing quantum effects in mechanical systems would, however, help to elucidate the boundary between the worlds governed by “classical” and “quantum” laws and to quantitatively verify the predictions made by quantum theory of measurements made on mechanical systems. This fascinating prospect has inspired researchers for decades to devise sophisticated devices expected to display quantum effects. However, they face two difficult experimental challenges: the elimination of thermal noise (such as the Brownian motion) and the detection of the minute position fluctuations associated with quantum effects. Recent research has focused on nanomechanical oscillators coupled to electronic measurement devices, but in spite of the low mass of the oscillators (making the quantum position fluctuations larger), the measurement sensitivity remained far from the Heisenberg limit.

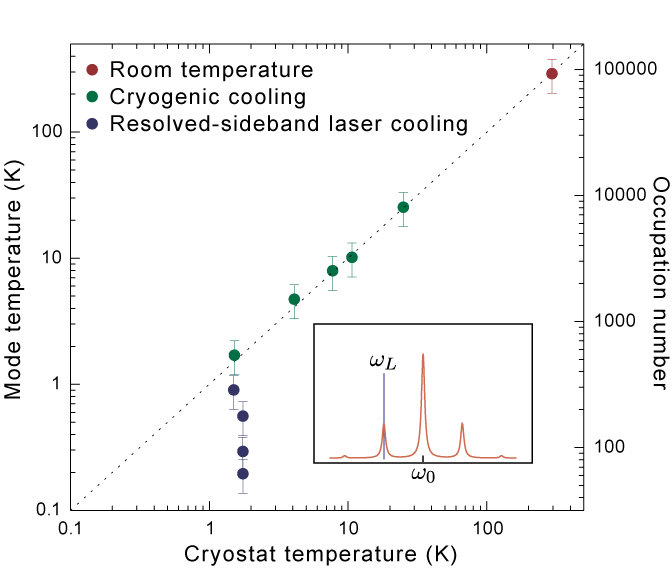

Tobias Kippenberg and his team instead developed optomechanical systems made out of small glass rings, about 0.1 mm in diameter, which constitute high-quality mechanical oscillators with extremely small dissipation, swinging at very high frequency between 65 and 122 MHz. To cool the oscillator they use a combination of two techniques: Traditional cryogenic cooling is implemented by bringing the structure in contact with a low-pressure Helium gas at a temperature only 1.65 degree above absolute zero. They verified that the device is cooled to the same temperature, due to the clever design of the cryostat based on buffer gas cooling. Then, they additionally implemented resolved-sideband laser cooling, a technique inspired by atomic physics, which was adapted by the MPQ group to cool also mechanical oscillators (1). In that manner, they reduced the temperature of the oscillator to 200 mK. This corresponds to an occupation of about 60 quanta of motional energy in the oscillator, the lowest value obtained with an oscillator of such a high mass.

To measure the minute fluctuations of the oscillator’s position, the researchers use optical interferometry. Ensuring that the noise in their measurement is as low as it can fundamentally be - determined only by the quantum fluctuations of the detected photon stream - the researchers achieved a displacement sensitivity on the level of a few attometers (1am=0.000000000000000001m) in one second averaging time. “But looking at the random fluctuations of the mechanical oscillator, we can also infer an upper limit to the degree to which our measurement has disturbed the mechanical oscillator, that is, we can quantify our measurement ‘backaction’,” explains Albert Schließer, PhD student on the experiment.

In this way the group has now proven that the employed optical measurement technique operates very close to the Heisenberg uncertainty limit. While still a factor of 100 above this fundamental limit, this is the closest approach yet demonstrated in an experiment. The ability to both cool the mechanical oscillator and make measurements close to the fundamental Heisenberg limit is pivotal for next generation experiments now set up at MPQ aiming to demonstrate effects like the quantum ground state, or quantum back action. [AS/OM]

Fig.: At room temperature, the mechanical oscillator has a very high thermal occupation of about 94,000 quanta (red point). But the combination of cryogenic cooling (green points), in which the oscillator is thermalized with a cold Helium gas, and resolved-sideband laser cooling (blue points) brings the oscillator occupation number down to about 60 quanta. The inset shows the laser frequency tuned to the lower sideband of the optical resonance of the optomechanical device.

(1) A. Schliesser, R. Rivière, G. Anetsberger, O. Arcizet and T. J. Kippenberg

„Resolved Sideband Cooling of a Micromechanical Oscillator“

Nature Physics, DOI 10.1038/nphys939 (2008).

Contact:

Prof. Dr. Tobias Kippenberg

Max Planck Institute of Quantum Optics

Hans-Kopfermann-Straße 1, 85748 Garching, Germany

Phone: +49 (0)89 32 905 -727 / Fax: -200

E-mail: tobias.kippenberg@mpq.mpg.de

http://www.mpq.mpg.de/k-lab/

Albert Schließer

Max Planck Institute of Quantum Optics

Phone: +49 (0)89 32 905 -264 / Fax: -200

E-mail: albert.schliesser@mpq.mpg.de

http://www.mpq.mpg.de/k-lab/

Dr. Olivia Meyer-Streng

Press & Public Relations

Max Planck Institute of Quantum Optics

Phone: +49 (0)89 32 905 -213

E-mail: olivia.meyer-streng@mpq.mpg.de